Christian Mysticism: 10 Must-Read Spiritual Books

Exploring the soul's ascent to God

True happiness comes in ascending to God, Beauty-itself—and over a thousand years of philosophers and saints offer to be your guide on this incredible journey.

What is Christian mysticism? It takes many forms, but this article looks at the impact of Platonic thought, especially the Symposium, and how Christian saints baptized many of the Platonic teachings on eros, human nature, the soul’s ascent to God, and the power of beauty. What emerged from these waters was a rich, beautiful Christian mysticism that coupled the best of philosophic insight with the truth of Jesus Christ.

The following list offers ten profound texts in chronological order and briefly summarizes their unique contributions and how they can help you ascend to God.

From the mystery of Christ as Logos to the “bright darkness of God” on Mount Sinai, Christian mysticism offers your soul tremendously beautiful concepts alongside practical steps for you to become beautiful as Christ is beautiful.

Many Christians would tell you that the Christian life is so much more than “be nice to people.” If you peel away the safe, tamed cultural versions of Christianity, there is an ancient mysticism that offers your soul a rich, vibrant path to true happiness.

The ascent awaits.

Reminder: you can support our mission and get all our members-only content for just a few dollars per month:

New, full-length articles every Tuesday and Friday

The entire archive of members-only essays

Access to our paid subscriber chat room

1. The Symposium, Plato

You may think it odd that a pagan text would be the first text on this list, but Plato’s Symposium set a spiritual template in the West for well over a thousand years. In his dialogue the Symposium (c. 385 BC), Plato presents man’s natural love, eros, and its desire to satiate in beauty and be happy. In what came to be known as the “ladder of love,” Plato gives us a picture of the soul ascending from lesser beauties to greater beauties until it satiates in the divine beauty-itself.

The text uses themes of eros, ascent, and beauty to understand anthropology and man’s calling to ascend toward the divine and be happy. It would be difficult to exaggerate the influence the Symposium had on later pagan and Christian thought.

Bereft of divine revelation, Plato is making observations on nature about the soul, its loves, and its path to the divine—and his observations can help you better understand the desires of your own soul and your search for true happiness.

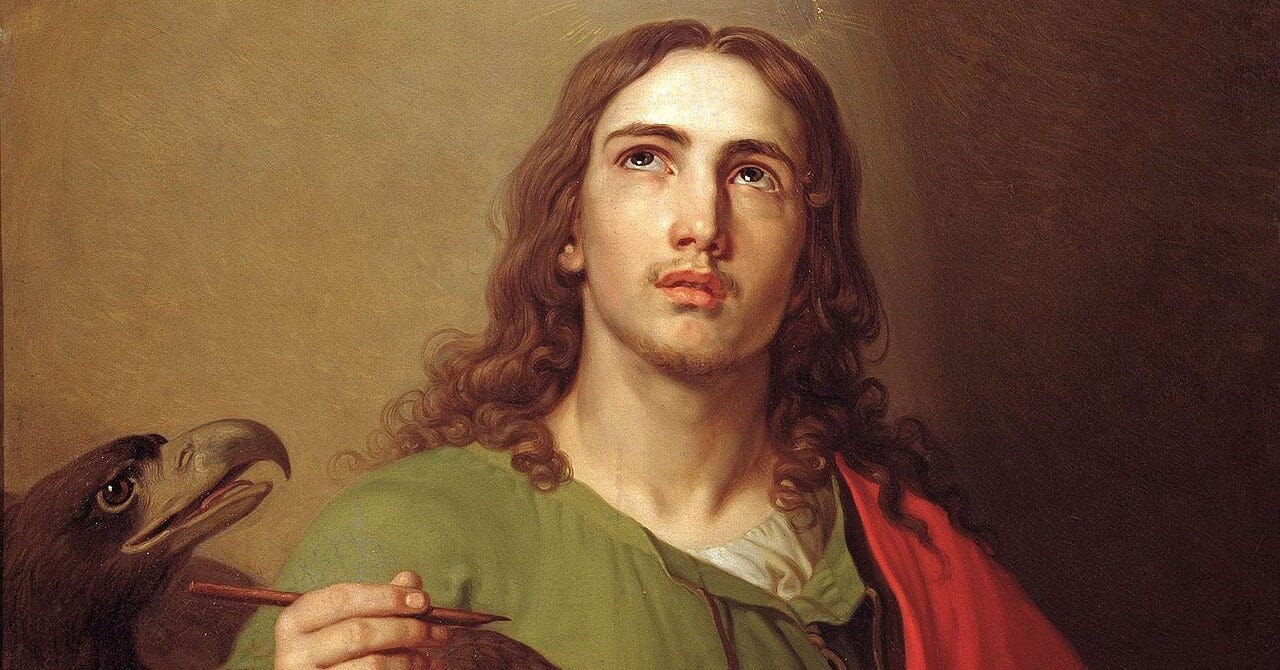

2. The Holy Gospel according to St. John

The Gospel of St. John is the mystic Gospel. The Gospel, written in Greek around AD 90, uses many Hellenistic motifs to describe the life and ministry of Jesus Christ.

Prior to Jesus Christ, Hellenistic and Jewish thought had come together—sometimes in violent ways, like in the Maccabees, but other times in beneficial ways, like the Book of Wisdom. Moreover, the first Old Testament canon, the Septuagint, was written in Greek, and it is the Septuagint with which Jesus and St. Paul were familiar (Luke 4:18-19; Matthew 1:23). You also had Hellenized Jewish thinkers, like Philo of Alexandria (25 BC to AD 50), already exploring Jewish theology and Platonism. While Hellenistic culture is not reducible to Platonism, Platonic thought made a significant impact on the Greek imagination and its subsequent imprints on Jewish and Roman thought.

Where can you see this imprint? There are two key examples in the opening of St. John’s Gospel. First, St. John famously makes the claim that the Logos is God.

In the beginning was the Logos, and the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made

The logos is an incredibly rich, multivalent word in Greek philosophy, which often means the “ordering principle of a thing” or the “account of something.” In other words, St. John uses a profound term in Greek philosophy to describe God, specifically the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, as the very order and rationale of creation itself.

Second, St. John makes a abundant use of the dichotomy between light and darkness, for example:

In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it (Gospel of St. John 1:4-5).

Many would point to St. John’s motif of light being analogous to how Plato uses it his works, like the allegory of the cave in the Republic.

If you want to bolster your interior life, to understand how you ascend to God, then you need to understand the Gospel of St. John—the heart of Christian mysticism.

3. The Enneads, Plotinus

Plotinus (AD 204-270) was a Greek philosopher who is widely held as the founder of and most significant thinker within Neoplatonism. While he rejected Christianity, Plotinus’ teachings made a significant imprint on later Christian thinkers, like St. Augustine and Dionysius. Again, the pagans can describe nature, but Christians believe that grace perfects nature; thus, keen insights into nature (philosophy) will always be beneficial to grace (theology).

Plotinus understood eros to be a cosmic force driving the soul’s ascent to the divine. Neoplatonism is a philosophy of ascent—it explores how the soul can ascend to the One, the ultimate source of reality. Like Plato, Plotinus saw the contemplation of beauty—from physical beauty to the eternal Idea of beauty—as a path to the divine, like the ladder of love in the Symposium.

People often do not handle beauty well—it causes them to go mad and fall into bestial desires; but Plotinus offers you beauty as a path to the divine—a path for your soul to become more excellent, more beautiful.

4. Confessions, St. Augustine

If you have not read this book, you must. It is one of the most beautiful texts in the Christian tradition, and arguably the first autobiographical text in the West. The entirety of Confessions (AD c. 397) is a prayer to God in which St. Augustine contemplates his youth and his eventual conversion to Christianity. St. Augustine, though writing in Latin, uses neoplatonic thought as a lattice work upon which to understand the Christian faith. He is, however, Christian first and neoplatonic second, as the former is the standard for the latter.

In the text, you will see the theme of beauty and how eros (or amor in Latin) must be taught to love beauty correctly. Going a step further than Plato’s ladder of love, St. Augustine will hold that God is Beauty-itself. In one of the most beautiful passages, he writes:

Late have I loved Thee, O Beauty so ancient and so new; late have I loved Thee! For behold Thou wert within me, and I outside; and I sought Thee outside and in my unloveliness fell upon those lovely things that Thou hast made…

The entire Confessions is a descent into sin and then an ascent into salvation. The main narrative ends with a mystical experience of ascent that is reminiscent of the ladder of love.

Christians hold this as one of the most beautiful texts in all of Christian history—and it is a text you can pray with and not just read.

Let St. Augustine’s journey be a light for your own.

5. The Life of Moses, St. Gregory of Nyssa

The Life of Moses (AD c. 380) is a beautiful and often neglected work. St. Gregory of Nyssa, the fourth-century Cappadocian early church father, draws from the neoplatonic tradition to provide an allegorical commentary on the life of Moses. St. Gregory, who is often regarded as the father of Christian mysticism, uses themes of eros, ascent, and light to explore the soul’s ascent to God.

One of the more unique contributions of this text is his commentary on Moses entering the darkness at the top of Mount Sinai and seeing God. St. Gregory describes Moses entering an intimacy with God that goes beyond all knowing or comprehension. Moses entered the “bright darkness of God,” a light so bright it is blinding, overwhelming the human capacity to know and understand—but is ecstatic and beatific.

Notably, St. Gregory states that St. John first “penetrated into the luminous darkness” of God.

St. Gregory of Nyssa’s use of neoplatonic themes to provide a beautiful commentary on the life of Moses offer you an introduction to Christian mysticism, an introduction to climbing toward God.

6. The Divine Names, Dionysius the Areopagite

Dionysius the Areopagite, sometimes called Pseudo-Dionysius, is most likely a monk in the late fifth to sixth century AD writing under the name of Dionysius, a well-educated Greek who converted to Christianity due to St. Paul’s preaching (Acts 17:34).

The Divine Names, drawing from Scripture and the platonic tradition, presents a beautiful reflection on the attributes of God, e.g., goodness and beauty, and how the soul is drawn by them to rise and satiate in the divine. It is a tremendous text that influenced Christian thought for centuries, including St. Thomas Aquinas (AD 1225).

One remarkable example of Christian thought perfecting pagan thought, is that the “divine beauty-itself” in the Symposium becomes under Dionysius God as Beauty-itself, as stated similarly in St. Augustine. Beauty is seen as equatable with the good, and since God is Goodness-itself he must also be Beauty-itself. To wit, he is the desire of all souls and that to which the soul yearns to ascend. Another remarkable development is that Dionysius explicitly defends the use of the term eros in Christian theology.

If you want a work you must read slowly and contemplate as you move along, then the Christian tradition would have few better options than the Divine Names.

7. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, St. John Climacus

Written by St. John Climacus (AD c. 579–649), a monk of the Sinai Monastery, The Ladder of Divine Ascent is a classic text in Christian monasticism and mysticism that outlines a spiritual journey toward God through thirty steps, reflecting themes of ascent, love, and divine beauty that resonate with Plato’s Symposium, Plotinus’ Neoplatonism, and Pseudo-Dionysius’ The Divine Names.

The ladder is an ascent that moves from renunciation of worldly desires (step 1) to ultimate union with God in love and contemplation (step 30). While its monastic tone is very different than many of the previous texts, it bears the same spiritual imprint as exhibited in the motif of climbing a ladder toward divine perfection with each rung of the ladder representing some new excellence in the Christian life. It is a practical, monastic guide to achieving union with God.

One unique contribution of the Ladder of Divine Ascent is that it inspired a beautiful icon of the same name—one of the best images capturing the spiritual reality of the ascent.

8. Four Centuries on Love, St. Maximus the Confessor

If you want an approachable, practical spiritual text this is the one for you. St. Maximus the Confessor’s Four Centuries on Love (written in Greek, AD c. 7th century) reflects themes of spiritual ascent, divine love, and the pursuit of God’s beauty. The work presents the ascent of the soul as a progression of love and excellence that purifies the soul and leads to union with God. The work presents 400 statements (hence, “four centuries”) commenting on sanctification and Christian excellence.

One notable teaching is how St. Maximus uses a Platonic anthropology and then shows how the Christian disciplines of fasting, almsgiving, and prayer perfect the three powers of the soul: appetitive, spirited, and intellect, respectively.

If you want a text you can carry with you and be reminded of the pursuit of Christian perfection through pity statements, this is one of your best options.

9. The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri

The Divine Comedy (AD c. 1320) is the Summa Theologica in poetry. It is the poetic zenith of the middle ages. It also exemplifies, amongst other things, two beautiful Platonic concepts: first, that the beauty of the beloved can lead the lover upward toward God; and second, the love is a cosmic force that animates the cosmos.

The former is seen in the Dante the Pilgrim’s pursuit of Beatrice through hell and up the mountain of Purgatory. Her beauty is a calling to ascend, to become better, to excel - reminiscent of how physical beauty can awake the ascent of eros in the Symposium.

The latter is exhibited in the final lines of the Comedy in which Dante lauds “the Love (l'amor) that moves the sun and other stars.” Love, for Dante, is a force that moves both the soul and the universe, which echoes the teaches found in the Symposium—a philosophical tradition Dante would know through the Neoplatonic tradition of St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas.

Christian hold Dante to be a master of the soul and its loves. It would be hard to find any better teacher to show you the path to God.

10. On the Nature of Love, Marsilio Ficino

If you have not heard of Ficino, you are probably not alone—as One the Nature of Love (AD c. 1469) is probably the most esoteric text on this list. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) was a Renaissance philosopher, priest, and scholar who led the Platonic Academy in Florence, translating Plato’s works and harmonizing Platonism with Christian theology.

The text is a fictional collection of speeches given by scholars gathered to celebrate Plato’s birthday (November 7th) commenting on the Symposium. It is tremendously beautiful, as it provides a Christian gloss on the text that set so many central themes of both Latin and Greek spirituality.

Ficino will speak of eros as a binding agent that governs the cosmos, that physical beauty is an invitation to love divine beauty, that beauty is the “flowering of goodness,” and that the daemons, like the one that aided Socrates, were angels moved by Providence.

If you have read Plato’s Symposium and you want a Christian gloss on the text, this work is certainly worth the read.

A World of Beauty Awaits

Eros, your natural love, is a desire to satiate in beauty and be happy. And Christians would hold, as did Plato, that your eros is infinite—it desires beauty at all times and always wants to be happy. But all the goods of this life are finite. Christian mysticism, however, would hold that only God, as the infinite Beauty-itself, can satisfy your heart. In fact, the infinite hunger of your eros was enkindled in you to lead you to the infinite beauty of God. As St. Augustine states, it is only in God that our restless hearts find rest.

Christians offer a rich tradition of mysticism that invites the soul to ascend to God and be happy.

Dcn. Harrison Garlick is a deacon, husband, father, Chancellor, and attorney. He lives in rural Oklahoma with his wife and five children. He is also the host of Ascend: The Great Books Podcast. Follow him on X at Dcn. Garlick or Ascend.

What about The Cloud of Unknowing?

Not sure if this one is relevant, but Boethius's The Consolation of Philosophy is a great read!