The Problem with Great Books Programs

How not to be a well-read relativist

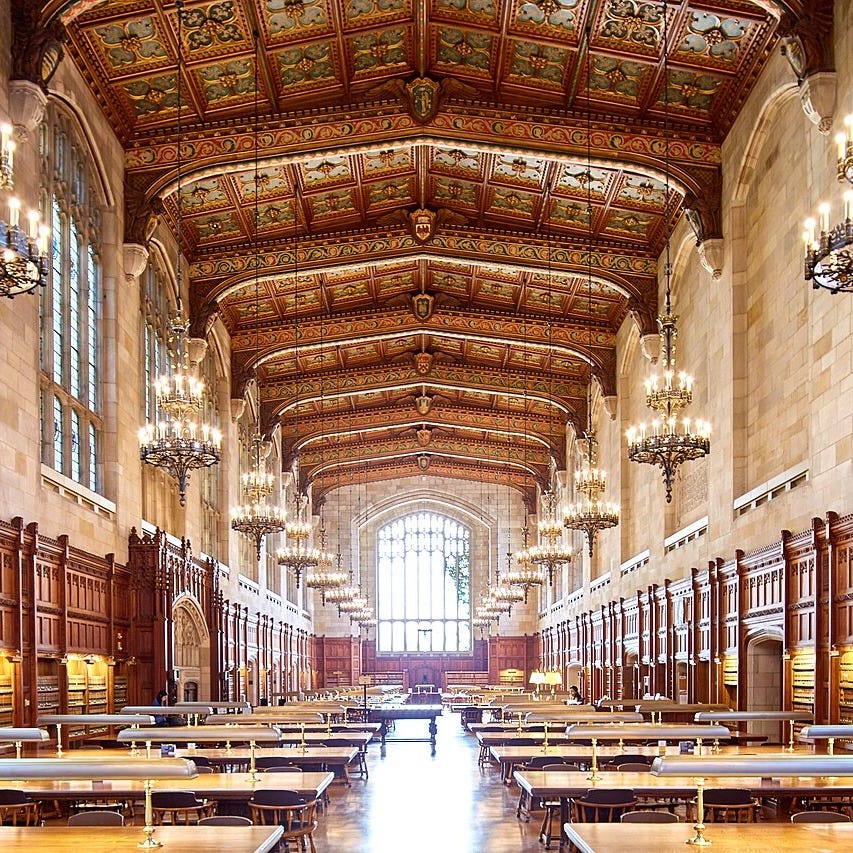

The West has undergone a practical book burning.

The liberal arts have collapsed. Education is now economic training. The goal is no longer to holistically form the soul according to what is real but to ensure the soul is a productive cog in a machine. All other considerations of who man is and his purpose in life are handed over to the anti-culture of relativism.

And amongst the debris of true education, many have turned to the great books.

Yet, can the great books be a remedy if they are infected with the same disease?

Many who read the great books become well-read relativists. In fact, it was many of the “great books” that led to the destruction of the liberal arts and to the reign of relativism. The great books are not enough.

Christians understand that truth is the conformity of the mind to reality, but modern man wants reality to conform to his mind. The great books can only help you reclaim your intellect from our predominant unreality if they are, in turn, rooted in and judged by what is real.

But how should you reconcile that you turn to the great books to teach you truth, yet you are to judge the great books by whether they teach truth?

Christians turn to an ancient belief to resolve this riddle…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get our premium content every week, upgrade for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

New, full-length articles every Tuesday and Friday

The entire archive of members-only essays

Access to our paid subscriber chat room

I. Reclaim your Education

“We are concerned as anybody else at the headlong plunge into the abyss that Western civilization seems to be taking,” wrote Robert M. Hutchins, editor of the 1952 Great Books of the Western World.[1] In order to “recall the West to sanity,” Hutchins, and his associate editor Mortimer Adler, compiled the fifty-four volume Great Books of the Western World series representing the primary texts from the greatest intellects in Western history.[2] From Homer to Freud, they saw these authors in a dialogue, a “Great Conversation,” that gave the West a distinctive character.[3] These authors, especially the ancient and medieval ones, had contributed to the rise of the liberal arts and to the belief that the liberally educated man was one who had disciplined his passions in pursuit of the good. As Hutchins observed, “the aim of liberal education is human excellence.”[4]

Yet, Hutchins saw the West was undergoing a practical book burning.[5]

The great books were being removed from Western education and with them any semblance of a true liberal education. Today, many people think they are receiving a good education when they attend a university—but they are not. It is evident that modern education is more a training than a formation of the whole person—it trains students for an economic function and delegates the holistic, human formation to a culture of relativism.

A college graduate is no longer expected to be “acquainted with the masterpieces of his tradition” nor the perennial questions into truth, beauty, or goodness.[6] We are deaf to the “Great Conversation.” We are cut off from the great treasury of our intellectual inheritance and now only vaguely aware it even existed.

The great books are an invitation to reclaim your education. They are a remedy to the privations of modern education and a salvageable substitute for our lack of a robust liberal arts formation. As Hutchins advocated, in reading the authors of the great books “we are still in the ordinary world, but it is an ordinary world transfigured and seen through the eyes of wisdom and genius.”[7] You are invited to the Great Conversation, to listen, and to add your voice to the pursuit of truth.

There is, however, a latent danger in the great books.

II. Avoid the Sins of your Age

In his 1647 masterpiece, The Art of Worldly Wisdom, the Spanish priest Baltasar Gracian, S.J., exhorts you to “avoid the faults of your nation.”[8] He explains: “Water shares the good or bad qualities of the strata through which it flows, and man those of the climate in which he is born.”[9] What is the intellectual climate in which you live and think? Christians warn that you live, as Cardinal Ratzinger observes, under a “dictatorship of relativism,”[10] and it contaminates every feature of your intellect. To have the requisite self-awareness and virtue to purge the common impurities of one’s own age, this relativism, is a “triumph of cleverness.”[11] Whether you think of the angel that led Lot out of Sodom or the man who returned to free those in Plato’s cave, the great books can be your guide in escaping the errors of your own age.

Writers like Aristotle or St. Boethius challenge your modern presumptions and stretch your imagination to encompass new perspectives on reality. Proponents of the great books claim you will better see your age for what it is and what led to this present culture (or anti-culture). In other words, the great books can inoculate you from relativism and its ills by exposing you to truth.

Relativism, however, is pernicious and infects even the remedies against it.

Can the great books lead to truth if the authors of the great books disagree on what truth is? In fact, many of the great books became “great” by rebelling against Western tradition. Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau all present new anthropological myths that are contrary to Genesis. Machiavelli rebels against Western ethics, and Marx rewrites the totality of how history should be considered. In short, the “great books” were chosen for their impact and not principally for their truth. It is a vital distinction.

The latent danger in the great books is that you simply becomes a well-read relativist.

It looks like this: before you are the greatest minds in the West, these minds disagree, therefore there is no reasonable expectation of truth. Even so-called conservative great books projects will refrain from saying one great book is better than another—they denounce any type of guidance to the great books, favoring a pseudo-neutrality that places dialogue over truth.[12]

As Dr. Patrick Deneen observes in his essay, “Against Great Books,” “I have come to suspect that the very source of the decline of the study of the great books comes not in spite of the lessons of the great books, but is to be found in the very arguments within a number of the great books.”[13] Many of the “great books” listed in the Great Books of the Western World are the same books that led to the crisis of education in the West. As Deneen notes, “the broader assault on the liberal arts derives much of its intellectual fuel from a number of the great books themselves.”[14]

How can the great books save you if the great books are part of the problem? The great books can be a remedy, but if applied incorrectly, the remedy for our failing liberal education becomes part of the disease.

The great books can help you avoid the errors of you age, but you cannot approach them through those same errors. Approaching the great books as some cosmopolitan relativist bears a contrary purpose than that of the traditional liberal arts. If the great books are our answer to the collapse of the liberal arts, then the great books must echo the true purpose of the liberal arts—of true education.

But what is the purpose of true education?

III. Conform your Mind to Reality

In his 1946 classic, The Intellectual Life, the French Dominican A.G. Sertillanges lays out the simple purpose of study: “The order of the mind must correspond to the order of things.”[15] He is drawing from St. Thomas Aquinas, who teaches that “truth is the conformity of the mind to reality.”[16] This is the purpose of the liberal arts, of the great books, and of all study: the understanding of what is true.

You must labor to conform your mind to the contours of what is real—so that the order of reality and that of your mind harmonize.

Yet, why is it important that you understand the purpose of study? Well, all things are judged good or bad according to their purpose (or telos, as the classical Greeks called it). You know a good knife must be sharp and a bad knife must be dull, because you know the purpose of the knife is to cut. Knowing the telos of something allows you to understand is quality—it is judged according to its end (telos). Moreover, because you know what a good or bad knife is according to its purpose, you also know what is a good or bad for the knife. A whetstone, for example, would be good, because sharpness helps to fulfill its purpose; whereas dulling it on concrete would be bad.

The same is true for education.

The telos of education is truth, the holistic formation of the whole soul to what is real. For education to be good, it must achieve this purpose. Many would argue that there is no better education for conforming the mind to reality than the liberal arts (i.e., classical education). And to the degree the great books are supposed to remedy our culture’s failing liberal arts, the great books too must be judged according to how they share truth.

Like a whetstone to the knife, a true great book will sharpen my mind’s understanding of reality. It is in obedience to this telos that you, like Sertillanges, judge your study and the study of the great books in particular. Not all great books meet this standard—as some labor to know what is real and other labor for what unreal. As Sertillanges teaches, “books are signposts” on the movement of the mind toward truth.[17] You approach such authors as a student approaches a teacher—ready for a tutelage in what is real.

If you are to help reclaim what was lost when the liberal arts fell, then the purpose of studying the great books must be the pursuit of truth. It was not relativistic dialogue that led Bl. Alcuin of York and Emperor Charlemagne to rebuild the West. Nor was it relativism that nurtured St. Thomas Aquinas or Dante. You are an inheritor of a robust pursuit of truth—a desire to satiate in the thickness of reality.

Yet, how does one judge what is true?

In other words, how should you reconcile that you turn to the great books to teach you truth, yet you are to judge the great books by whether they teach truth? Are you the standard? Are you the arbiter of what is real? What was the principle of truth for the liberal arts?

There is no neutral.

Christians see the answer to this riddle rooted in a careful reading of the New Testament, one that peels back and sees a profound truth of who Jesus Christ is.

It is only then that the tutelage of the great books allows your soul to stand against the anti-culture of relativism.