Why Do We Call God Good?

A Christian look at the Euthyphro Dilemma

It is one of the most important questions in Western thought.

Is God good because He adheres to an external, objective standard of goodness? Or is God good because whatever He wills is good? Why do we call God good?

You may think this sounds like a word game or some obscure philosophical discourse, but it is a fundamental question about the nature of the divine—and thus of reality and how you should live your life.

Plato was the first to raise this question explicitly in his dialogue the Euthyphro. He asks it of the Greek gods, the pantheon, and it brilliantly opens the door to an intelligible reality where philosophy is possible.

Yet, Plato’s brilliant critique of the Greek gods seems to pose a significant difficulty to the Christian God as well. How do Christians answer the question: why do we call God good?

Even more so, Plato’s critique reveals two opposite, competitive ways of interpreting reality, of determining what is good and what is truth.

Most people do not even know they are using these ways to understand the world, they just find it normative, but if you are to ascend in your spiritual life, you have to take ownership of this fundamental question: how do you interpret reality?

Plato’s question is one of the most important questions for a reason.

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get our premium content every week, upgrade for a few dollars per month. You’ll get:

New, full-length articles every Tuesday and Friday

The entire archive of members-only essays

Access to our paid subscriber chat room

The Problem of Piety

Shortly before his trial and execution in 399 BC, Socrates runs into a young man named Euthyphro outside the King Archon’s court, a judicial power that adjudicated religious matters in Athens. Euthyphro presents himself as a prophet, a man with esoteric knowledge of the gods, and Socrates, who has been charged with the crime of impiety, asks Euthyphro to teach him what piety is. Though Socrates knows more than Euthyphro does, this Socratic irony opens up a conversation between the two atypical, Athenian religious thinkers on the gods and piety.

But wait… what is piety? Piety for the ancient Greeks is a profound concept that orders man’s relation to the cosmos, the ordered whole. As seen in Homer, Aeschylus, and more, the ancient Greek had to be pious toward his family, his polis (city-state), and his gods. The threefold piety was an expression of gratitude, an expression of what one owed to one’s family, polis, and gods—and the debt was expressed in that order, from lowest to highest.

However, what piety demanded was not always clear.

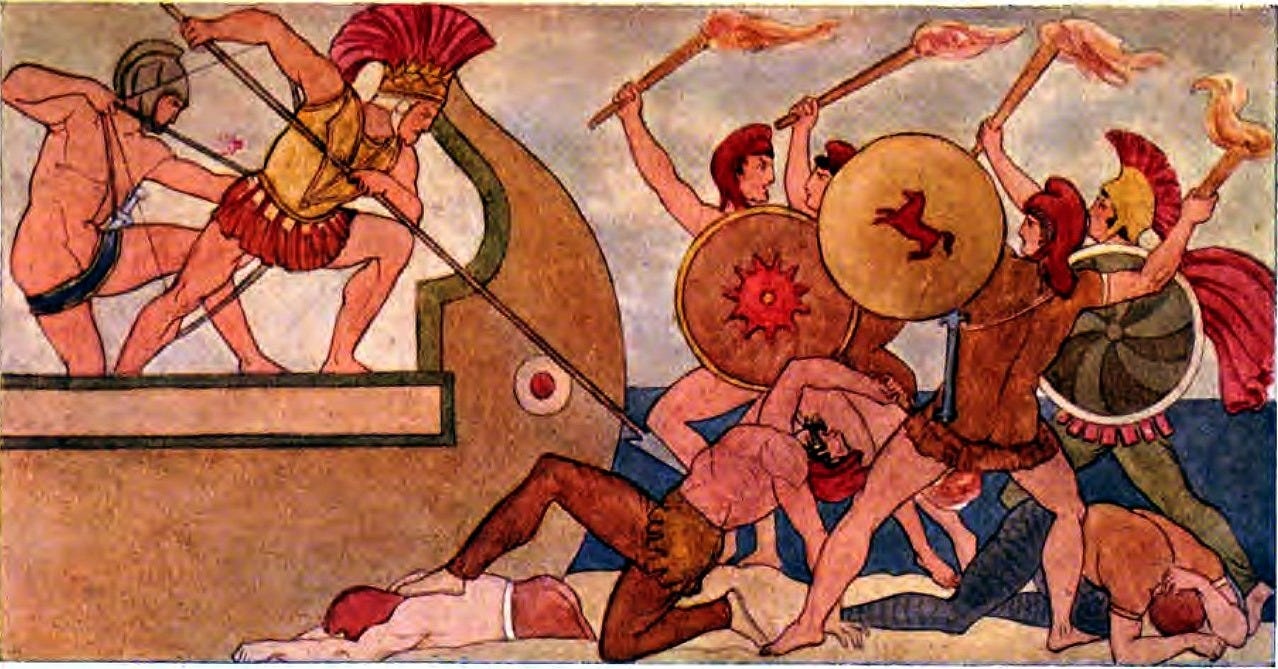

For example, in Homer’s Iliad, several of the gods support the Achaeans in the Trojan war, while several others support the Trojans. It was not possible to be pious toward the gods but only toward some gods—as the gods disagreed about justice. Further, in Antigone, Antigone and King Creon disagree about what piety demands when it comes to burying a traitor—and both sides appeal to the gods for support.

Piety is an essential virtue for the ancient Greek, but Socrates wants a clearer definition—he wants to understand the essence of what piety is.

And in this search, he gives us one of the most famous questions in all of Western philosophy.

The Euthyphro Dilemma

The most famous part of the Euthyphro dialogue is known as the “Euthyphro dilemma,” in which Socrates asks the following:

“Is the pious being loved by the gods because it is pious? Or is it pious because it is being loved by the gods?”

If this confuses you, no worries! It can be tricky at first—but it is worth your effort. The statement is a statement of causality—what is the cause and what is the effect. The dilemma has two parts or “horns.” The first part asks whether the pious is something objective loved by the gods, i.e., “is the pious being loved by the gods because it is pious?” In this horn, the gods are adhering to something that is objective, real, and superior to them. For example in Antigone, Antigone argues that the gods want her to bury her brother, the traitor, because there are laws that even the gods obey. Piety, in this horn, is a set concept loved by the gods.

The second horn of the dilemma asks “is it pious because it is being loved by the gods?” This thesis is the opposite of the first horn, as here what makes something pious is that the gods love it—it is not objective but subjective. What makes something pious is the will of the gods. For example, in the Greek tragedy The Bacchae, the god Dionysius is licentious and cruel, but people are punished for their lack of piety toward him—why? Because it does not matter if the human thinks the divine is falling short of some universal standard of goodness and justice, what matters is that it has been willed by a god—and whatever the gods will is pious.

The two horns are mutually exclusive and present contrary philosophical views: objective versus subjective. If the idea of “piety” is unclear, the Euthyphro dilemma can be re-written concerning the good: “Is the good being loved by the gods because it is good? Or is it good because it is being loved by the gods?” Is what is good an objective, universal reality that can be known or is the good a subjective, atomized reality determined by the gods (or a god)?

But this dilemma is not reducible to some Greek thought experiment—it is at the core of how you live your life. Every moral decision you make is filtered through this dilemma—and many political debates and vehement disagreements are because people are coming from opposite sides of this dilemma.

Moreover, how does a Christian answer this dilemma? Is God good because he adheres to a universal, objective standard of justice? Or is God good because whatever He wills is good?

You think the Euthyphro Dilemma is a philosophical brainteaser about the Homeric gods, but it is actually an invitation for you to have intimate knowledge on the nature of God and your soul.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Ascent to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.